Since the 2021 DIRT Report was published last fall, a debate has stirred about the limits of damage prevention the way it’s done now.

In October, the Common Ground Alliance (CGA) released its report on 2021 submissions to its Damage Information Reporting Tool (DIRT). The results show cause for concern. Total damages reported to DIRT barely budged in 2021. The trendline has flattened since 2019. Using the process most commonly in place across North America, sustained effort isn’t translating into fewer damages.

Of course, there are proven ways to make big improvements in damage rates. Still, the broad results are sobering, and they have spurred important questions about the damage prevention process — including possible changes that could bring huge gains:

- Is the current damage prevention process working at its very best?

- What about the approach is failing to drive down damages further?

- What emerging technologies or strategies could lead the industry out of its stagnation?

Are we at peak damage prevention (the way it’s done now)?

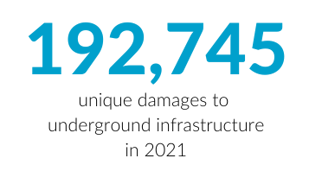

Based on submissions to the 2021 DIRT Report, United States infrastructure sustained 192,745 unique damages in 2021. Using apples-to-apples data submitted by facility owners over the past several years, the report shows a 1% increase in damages per 1,000 transmissions from 2020. An increase is never good, but this small bump merely offsets the 1% decrease from the previous year. The overall trend remains stable.1.

At the same time, construction spending rose by $50 billion in 2021, but damages per dollar barely moved — from 0.098 to 0.101.

Standard root causes also haven’t changed much in recent years, with the top three forming over 50% of all damages:

- No notification made to 811 center;

- Facility not marked due to locator error; and

- Excavator failed to maintain clearance after verifying marks.

Together, these figures show clear stagnation in key metrics for damage prevention. Despite best efforts with their current methods, infrastructure operators struggle to improve their numbers. The results have led one 2021 DIRT Report author to highlight the need for changes to the standard process and widespread adoption of next-generation technologies to push the industry over the hump.

‘The problem is the system itself’

Jemmie Wang is a prominent figure in the damage prevention community. A former executive at USIC and former co-chair of the CGA Data Committee, he’s the current lead author of the DIRT Report. He also delivered a presentation at the 2022 Midwest Damage Prevention Training Conference that highlights the current stagnation in damage prevention.

“[Damage prevention] is fundamentally the same process as it was 35 years ago,” he says. “Right now, one of the biggest barriers to more improvements is the system itself.”

The normal damage prevention workflow starts with a locating request. An engineer, an excavator, a utility, or a homeowner calls or clicks in a ticket to their local 811 center. The 811 operator then notifies facility owners of the intent to dig near their infrastructure, and those owners hire and dispatch locators to mark the area.

Using this process, facility owners — gas, electric, water, sewer, and telecom companies — spend roughly $5 billion annually to prevent damages. They pay out another $1.5 billion for hits that fall through the cracks in this system (most commonly the missed notifications, locator errors, and excavator errors cited above).

“I ask you this question,” says Wang. “If I increase spending on damage prevention by 10% doing it the same way we do now, do you think we will have 10% fewer damages?

“What about 50%? Would damages be halved? There’s no way. No one believes that.”

The costs and incentives of damage prevention are working against further improvements as well. If facility owners increased their spending by 10%, they would spend an additional $500 million. But a 10% improvement in damage prevention would only save them $150 million — a net loss of $350 million, or a 70% negative return on investment.

The costs and incentives of damage prevention are working against further improvements as well. If facility owners increased their spending by 10%, they would spend an additional $500 million. But a 10% improvement in damage prevention would only save them $150 million — a net loss of $350 million, or a 70% negative return on investment.

Wang adds that facility owners only bear the costs of roughly 10% of the damages to their infrastructure, the rest falling on excavators or locators.

“So, they’d end up paying $500 million more to reduce damages by $15 million,” he says. “That’s crazy.”

Why aren’t infrastructure damages falling nationwide?

While the damage prevention process has largely remained the same for 35 years, significant improvements were made in the 2000s and early 2010s. In 2005, 811 became a national three-digit number that allows anyone in the United States to call in a request for infrastructure location. Apple released its first iPhone in 2007 and HTC released the first Android phone in 2008. The easy communication of these devices coupled with their onboard GPS significantly upgraded the capabilities of locators.

Smartphone sales finally outpaced regular cellular phone sales in 2013. Since then, Wang notes that little has fundamentally changed the work of damage prevention.

It’s true that changes in data and communications technologies plateaued in tandem with damages to underground infrastructure. In 2018, Pew Research published an article highlighting the lack of growth in internet use and device ownership in the U.S. Smartphones, mobile internet, and GPS were all “quantum leap improvements” for locators, according to Wang, but more recent technologies have yet to translate into similar results. Rather, current technologies have taken damage prevention efforts as far as they can go and, to see real improvements, the system needs to change.

“You can’t just ‘locate’ harder, work more. It’s got to be something more intelligent.”

What can facility owners do to move damage prevention forward?

Even if the costs are currently misaligned, there are clear reasons to pursue fewer damages to infrastructure. Every damage poses a safety risk to workers and communities. Each time a backhoe strikes a gas line, it risks explosion, evacuation, and release of methane into the atmosphere.

But what can companies do? Wang envisions a new damage prevention workflow that leverages emerging technologies and processes to prioritize locations and interventions.

“Instead of using this shotgun approach, where the ticket called in at this farm in the middle of nowhere is treated as important as this ticket near this airport or substation, you can use software to allocate resources more intelligently,” says Wang.

His proposed workflow has several adjustments that could bring damage numbers down. He suggests 811 centers share their GIS databases with qualified excavators, so they can confirm the lack of underground assets in low-risk areas themselves. Then, they could dig safely without needing to wait the required 48 hours — lessening the burden on overwhelmed locators. With a more structured understanding of priorities, facility owners could send their inspectors to dig sites with difficult terrain or inexperienced work crews.

Wang also thinks the more strategic interventions in this workflow would improve the timeliness of locates too, which could advance damage prevention even further.

***

If nothing else, the 2021 DIRT Report shows that national damage prevention efforts have gained little ground in recent years. Yet, damage trends are not equal across the United States. Certain states (and utilities) have seen more improvements than others, even in spite of growth in construction spending. But limitations of reporting make it difficult to determine the exact cause for improvements in one area vs. another.

As construction expands due to funding from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the U.S. finds itself in a natural experiment. With more construction placing more infrastructure in jeopardy, future DIRT Reports may show which states are doing better than expected — and which processes and technologies they’re using to get stronger results.

Want more analysis about the 2021 DIRT Report and the state of damage prevention? Join our mailing list below.

1. Submissions to DIRT are voluntary and not necessarily comprehensive of all infrastructure damages across North America.