High-energy control assessments (HECA) are a new strategy to improve worker safety on construction and utility job sites. They are a process that field crews and inspectors can use to ensure all high-energy hazards on site have a matching control to reduce or eliminate energy that may contact workers.

But what exactly is HECA? How does it keep utility workers safe? And how can utilities put these assessments into practice to prevent more serious injuries and fatalities?

Let’s take a look to find out more about this new tool and why it’s so effective at protecting utility workers on the job.

What is HECA and how does it work?

High-energy control assessment (HECA, also known as energy-based observation) is a step-by-step process for confirming that all sources of high energy on a job site have direct controls in place. It was developed by Dr. Matthew Hallowell and Dr. Elif Erkal of the Construction Safety Research Alliance (CSRA), a group of industry leaders and academics dedicated to construction safety research and serious injury prevention.1

HECA is based on energy-based hazard recognition — the idea that every injury is the result of an unwanted release of energy that comes into contact with workers’ bodies.2

While every injury is caused by a release of energy, serious injuries and fatalities (SIFs) arise from releases of high energy — those that contain over 500 foot-pounds. For example, a cinder block falling off a one-story building contains enough kinetic energy to cause a SIF.3

Fortunately, sources of energy can be controlled. (By definition, safety is the presence of controls, rather than the absence of mistakes.) Direct controls are actions that workers can take to reduce or eliminate the energy associated with these high-energy hazards. For example, a fall arrest system is a direct control for gravity. A barricade alongside a busy highway is a direct control for the kinetic energy of motor vehicles.

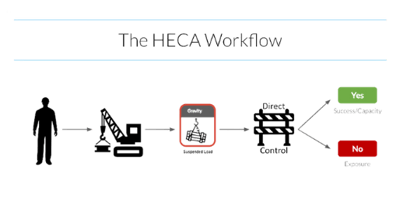

In a HECA, an inspector checks every high-energy hazard on a job site to make sure a corresponding direct control is in place. If the high-energy hazard is controlled, it’s considered a success. If it isn’t, it’s considered an exposure (and the inspector has identified an opportunity to put a safety measure in place before starting work).

By conducting a HECA, inspectors follow a systematic approach to confirm that workers are limiting their exposure to high-energy hazards. They also collect critical data about risks, energy sources, and high-energy exposures they can use for analysis and continuous improvement.

How does HECA keep workers safe?

HECA is singularly effective at keeping workers safe because it optimizes and standardizes a process that field crews have long performed without a focus on quality.

“Workers have always conducted inspections, but for years they’ve looked for safety hazards across the board — slips, trips, and falls or that sort of thing,” says James Upton, former vice-chair of serious injury and fatality research at the CSRA (and current Urbint director of safety operations).

.png?width=400&height=393&name=Energy%20Wheel%20(Color).png)

“HECA is a way of adapting this process to concentrate on high energy — the STKY, the Stuff That Kills You.”

By design, HECA forces workers to pay close attention to high-energy hazards — the ones disproportionately likely to result in a SIF. Rather than worrying about total recordable incident rates that consider scrapes and bumps equivalent to life-altering or life-ending injuries, HECA only concerns itself with the most hazardous sources of energy.

It also ensures consistency. HECA puts into practice ideas brought forth in The Checklist Manifesto, Dr. Atul Gawande’s 2009 bestseller about the strength of checklists for helping complex processes flow consistently, correctly, and safely.

Humans have limited attention that drives our brains to take shortcuts, especially in familiar situations, such as jobs we perform every day. In complex scenarios like a utility work site, these shortcuts can cause us to skip over important details, like a properly attached safety harness. As with checklists, HECA supports workers with a systematic approach to confirm that no steps in safety protocols have been accidentally overlooked.

HECA helps field crews identify more uncontrolled hazards in the moment, but it also serves as a useful metric for tracking a safety program’s continuous improvement. Once an inspector completes a HECA, they can calculate the ratio of control successes vs. exposures to arrive at a score. By tracking and analyzing HECA scores across projects, territories, business units, or time, utility management can gain critical insight into safety trends affecting their workers. They can then dedicate attention and resources to the problem areas that need them the most for continuous improvement, whether it’s trouble with arc flashes in Atlanta or suspended loads in Boston.

“Over time, HECA trends will allow benchmarking and point to where the safety investments can actually make a difference,” says Dr. Erkal.

How do I apply HECA on a job site?

HECA is designed to become a standard part of your job safety program. To get the most value from it, utility crews can follow a three-step process.

1. Identify your high-energy hazards

Because HECA is only concerned with high energy, field crews must first identify all sources of high energy present on their job sites. Hazard identification can happen as part of a tailboard meeting or pre-job safety briefing, or it can happen any time a worker spots a hazard. Crews can use tools like the Energy Wheel or Urbint for Worker Safety (which incorporates the Energy Wheel concepts) to support their hazard recognition. (After all, work crews can only identify about 45% of hazardous energy sources without a tool to help them.)

For more information about the Energy Wheel and high-energy hazards, explore these resources from Urbint:

2. Conduct the assessment

Using a HECA form or interactive app, inspectors conduct the assessment by checking all high-energy hazards identified by the work crew. For each one, the inspector must confirm that each hazard has a direct control that meets three criteria:

- The control is specifically targeted to the high-energy source. (For example, a set of egress stairs targets excavation cave-ins. A plan to climb out at the first sign of trouble does not.)

- It effectively mitigates exposure to high energy. (For example, an exclusion zone around a suspended pipe will prevent the load’s energy from striking a worker in the event of a failure. A hard hat will not.)

- It works even if someone makes a mistake. (For example, a fall arrest system prevents a worker from falling from a height, even if they slip or trip.)

If a control meets all three criteria, inspectors mark that high-energy hazard as “success”. If not, the high-energy hazard is uncontrolled and it gets marked as “exposure.” Then, a crew must find and implement a control before starting work safely.

3. Calculate your HECA score

After the assessment, inspectors can calculate the HECA score by dividing hazards marked as “success” by the sum of all hazards marked both “success” and “exposure.” This number gives you an overall percentage of high-energy hazards left uncontrolled prior to conducting a HECA.

This HECA score gives utilities vital information they can use for long-term continuous improvement, such as tracking the consistency of controls implemented across different projects or territories. This information shows utilities which of their initiatives are working effectively and which persistent safety issues need more resources or attention.

Although HECA is new, it is already gaining strong attention from utility leaders. The Edison Electric Institute is championing HECA to its members, and many utilities who have oriented their safety programs around high energy are now incorporating HECA into their processes.

As the industry further shifts its safety focus toward energy-based hazard recognition, the systematic process of HECA offers a simple yet effective way to target the real causes of SIFs for utility workers, keeping them safer on site and even safer in the future.

***

Want to know more about HECA, the Energy Wheel, high-energy hazards, direct controls, and how to apply them on a job site? Check out our full blog series on energy-based hazard recognition:

- What Is The Energy Wheel?

- High-Energy Hazards: The 13 Most Common Causes of Serious Injuries and Fatalities for Utility Workers

- 6 More Common Causes of Serious Injuries and Fatalities for Utility Workers

- How to Use the Energy Wheel on the Job

1. Oguz Erkal, E. & Hallowell, M. (2023). Moving Beyond TRIR: Measuring and Monitoring Safety Performance with High-Energy Control Assessments (HECA). Professional Safety Journal. Accepted for May issue.

2. Albert, A., Hallowell, M. R., and Kleiner, B. M. (2014a). “Enhancing Construction Hazard Recognition and Communication with Energy-Based Cognitive Mnemonics and Safety Meeting Maturity Model: Multiple Baseline Study.” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 140(2), 04013042.

3. A standard 8” x 8” x 16” cinder block weighs approximately 38 lbs. Using the formula for kinetic energy KE = ½ mv2 and the free fall calculation of v = v0 + gt (where g = 32.17 ft/s2), a cinder block in free fall achieves a velocity of 30.02 ft/s over 14 ft, the average height of a single-story building. This results in a hazard with 721.32 J of kinetic energy or approximately 532 foot-pounds.